Dungeons & Dragons, Storytelling

No more bad boxed text!

If you’ve ever read an adventure module, you’re familiar with the concept of “boxed text”. It’s descriptive text, put there by the module’s author, so that you can read it aloud to describe an area, character, or event. It helps get everyone at the table on the same page, in terms of what the scene looks like, who’s in it, and what’s going on.

But you can’t always rely on boxed text. A lot of times, you’ve got to make things up as you go along.

So how do you describe a compelling scene for the folks around your table? How do you project the images that are inside your head out into the world, and convey as much detail as possible without droning on for hours and hours?

The answer is simple:

Sensory imagery!

“What is sensory imagery,” you ask? Good question!

If you’re more of a visual type, check out the video just below. If you’d like to read, carry on!

Sensory imagery is the use of descriptive language to create mental images. This is done by appealing to our sense of sight, hearing, taste, touch, smell, or movement. The pan isn’t hot, it’s “searing”. The light isn’t bright, it’s “blinding”. The smell isn’t bad, it’s “rancid”. The punch didn’t just “hurt”, it “made you see stars”.

Here are a few tips you can use to step up your game descriptions, whether you’re writing them ahead of time or coming up with them on-the-fly.

Appeal to the senses

Don’t just tell your players WHAT is in front of them, tell them what it smells like; how big or small it is in relation to other things in the scene; what it sounds like. If they can touch it, tell them what it feels like–rough, smooth, wet, whatever.

This is what your teachers meant when they said “show, don’t tell.”

It’s not a “small goblin”. It’s a “Grotesquely pungent green man, standing no higher than your hip, with a long oily nose and pointed ears, whose sneering grin reveals yellow teeth to match his angry eyes.”

Use comparisons

Comparisons are descriptive shortcuts where you take something in your scene and you relate it to something your players are familiar with. Remember my “kaleidoscope of flowers” from the video above? I didn’t have to describe the individual colors of each flower, or how many there were in the meadow. I relied on your experience with a kaleidoscope to do the job for me.

If you’ve ever been taught creative writing in school, the comparisons you’ll see most are metaphors and similes. Similes are the easiest–you compare two things using the words “like” or “as”. “He’s as tall as a tree,” or “He’s as fast as a cheetah.” We all have a sense of how big trees are, and most of us have seen cheetahs running on television, so we can use these comparisons as shortcuts to avoid describing minute details of how tall or fast a person is

Use personification

Personification is where we give human qualities to nonhuman things, like how in the video I described the bees in the meadow as “dancing”. It doesn’t have to be a physical act like that, either–it can be a feeling or mood. A bright light can be “angry”, or a dying candle can flicker “sadly”. A single cloud in the sky can be “lonely”, or the wind can “howl its objection” to your character’s shelter in a storm. The possibilities with personification are endless, and you’d be amazed at what you come up with when you take a human trait and tie it to a nonhuman thing.

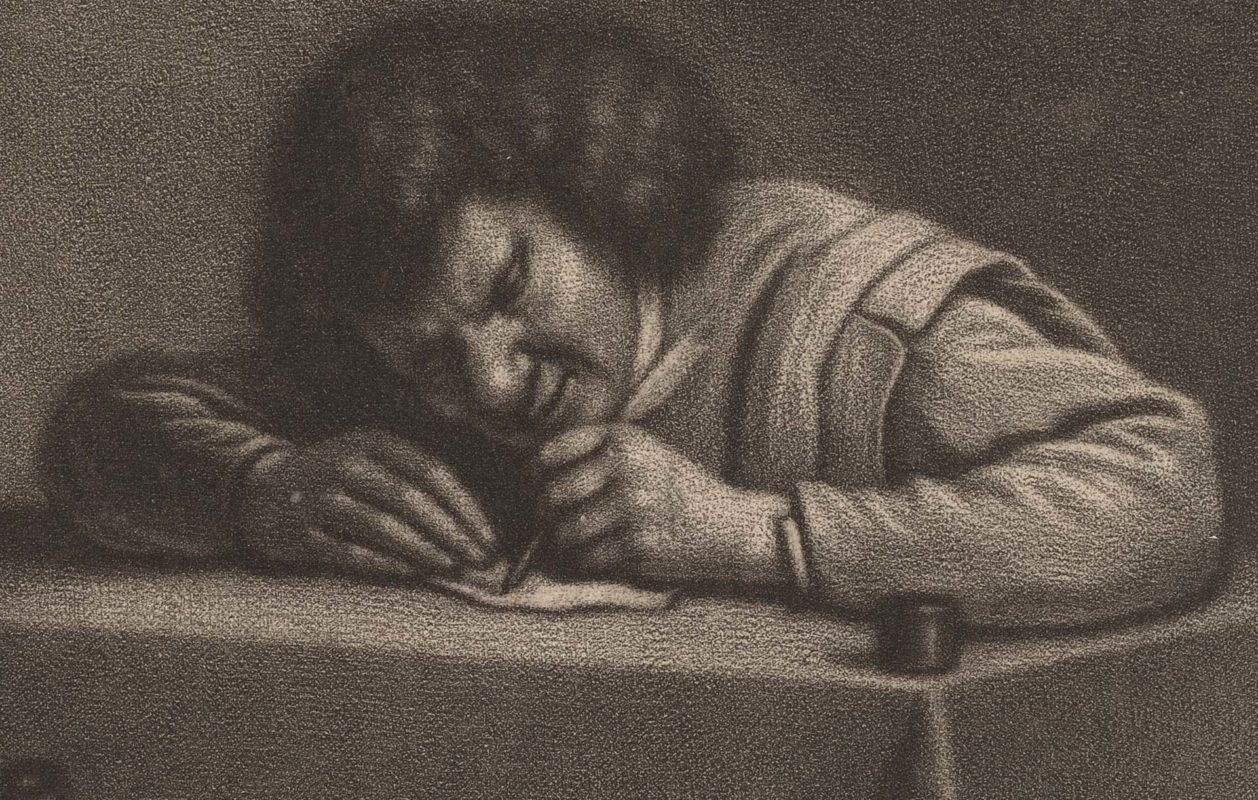

Close your eyes

Seriously. When I’m describing a scene on the fly for my players, I’ll lean forward on my table and close my eyes. Then, I imagine the scene and begin telling them about it. It’s like there’s a movie that only I can see but I want them to know what’s going on–not only in a dry factual way, but on an emotional and sensory level as well. By closing your eyes, you can shut out the visual world around you and focus on the imaginary world in between your ears.

All of these techniques come from creative writing–you’ve likely heard all of them before in school, or you’ve read about them in books.

The key here is practice. And if you’re improvising instead of writing things down ahead of time, don’t be afraid to falter or fall over your own words sometimes. I guarantee you’re doing better than you think you are.

Oh, and reading; lots of it. And not just passive “I’m gonna read this and forget about it in five minutes” reading, either. I mean, active reading with questions like “How did the author make that sound so good? Why did I feel like that? What sorts of senses did they appeal to here, and how?”

All that crap from high school English class that everyone hated doing.